Calling all functions

1. avr-gcc function calls

Brief review of day10 content.

-

Open the GCC Wiki page for

avr-gcc

1.1. Register Layout

- R0

-

When the compiler wants to use a register for some temporary purpose, it first uses R0.

- R1

-

Assumed to always be zero when read.

1.1.1. Call-Saved Registers

R2 — R17, R28, R29

Put it back the way you found it after you’re finished.

-

Save the value of the affected register (to the stack:

push r5) -

… do your thing …

-

Restore the value of the affected register (from the stack:

pop r5) -

Then and only then can you

retorreti

1.1.2. Call-Used Registers

R18 — R27, R30, R31

The compiler is under no obligation whatsoever to remember what these registers held before writing to them.

| Therefore an interrupt service routine (ISR) must save and restore these registers, if used. |

Also note that the pair of registers R31 : R30 is known as Z on the AVR and has sometimes special uses.

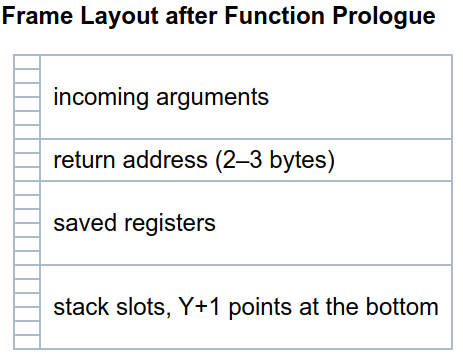

1.2. (Stack) Frame Layout

avr-gcc decides which specific registers to use near the end of the compilation process, hence this talk about “pseudo registers” — it’s a CS thing.

Notice how R29 : R28 are assigned — i.e. don’t use these registers!

2. Example watching avr-gcc do its thing

avrgcc-functions.ino using the Arduino IDE/*

* ECE 422

* Calling functions

*/

/*

* Global variables placed in SRAMj

*/

volatile char a, b, c, d;

volatile int out; // holds function return values

/*

* The "__attribute__ ((noinline))" business is GCC-specific syntax

* saying to NOT optimize by inlining the code at the point of use.

* We *want* to see the rcall / ret happening!

*

* https://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc/Function-Attributes.html

*/

char __attribute__ ((noinline)) fOne(char first) {

return first + 1;

}

char __attribute__ ((noinline)) fTwo(char first, char second) {

return first + second + 1;

}

char __attribute__ ((noinline)) fThree(char first, char second, char third) {

return first + second + third + 1;

}

char __attribute__ ((noinline)) fFour(char first, char second, char third, char fourth) {

return first + second + third + fourth + 1;

}

void setup() {

pinMode(LED_BUILTIN, OUTPUT);

a = 2;

b = 4;

c = 16;

d = 64;

}

// the loop function runs over and over again forever

void loop() {

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, HIGH); // turn the LED on (HIGH is the voltage level)

delay(1000); // wait for a second

digitalWrite(LED_BUILTIN, LOW); // turn the LED off by making the voltage LOW

delay(1000); // wait for a second

// call function with one 8b argument

out = fOne(a);

// call function with two 8b arguments

out = fTwo(a, b);

// call function with three 8b arguments

out = fThree(a, b, c);

// call function with four 8b arguments

out = fFour(a, b, c, d);

}-

Verify/Compile this sketch

-

Sketch → Export compiled Binary

-

Open the

avrgcc-functions.ino.lstfile in a worth text editor and turn on syntax highlighting.

SAVE-AS so you are working on a copy of the file!

By now, you are somewhat familiar with reading assembler syntax.

The .lst file syntax is a combination of comments, notes, information, and the assembly code that GCC compiled to from the source C/C++ code.

In the Arduino IDE, turn on Verbose output to see the commands that generate the listing file.

avr-objdump

3. Interrupt Service Routines

Introduction to avr-libc’s interrupt handling

It’s nearly impossible to find compilers that agree on how to handle interrupt code.

Even though we are presently using assembly for programming our AVR-based ATtiny85, it is useful to be aware of how a C/C++ compiler deals with interrupts.

Open up the AVR libc documentation about interrupts:

https://www.nongnu.org/avr-libc/user-manual/group__avr__interrupts.html

4. References

GCC special attributes https://gcc.gnu.org/onlinedocs/gcc/Function-Attributes.html

Jaywalking Around the Compiler — Jason Sachs, EmbeddedRelated.com. Mixing C and assembly requires understanding the compiler’s assumptions it uses.